Developing a Novel Dating Technique for Arctic Faults

A workflow that bypasses expensive chemical separation to make high-precision fault dating faster and cheaper.

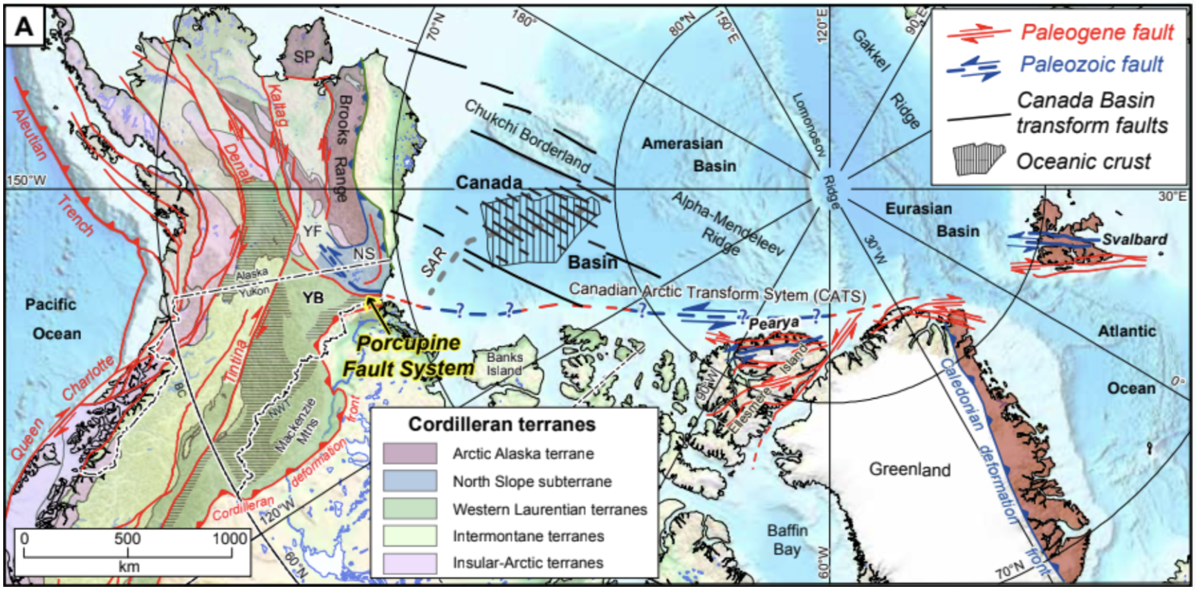

The Arctic Ocean is the last major ocean basin on Earth whose origin story remains unknown. There's a leading theory that the Porcupine Fault System in Alaska shifted during the age of the dinosaurs to let the ocean open up, but proving it requires knowing exactly when that fault moved.

Geologic map showing the Porcupine Fault System (yellow arrow), a key structure in the hypothesis regarding the opening of the Arctic Ocean.

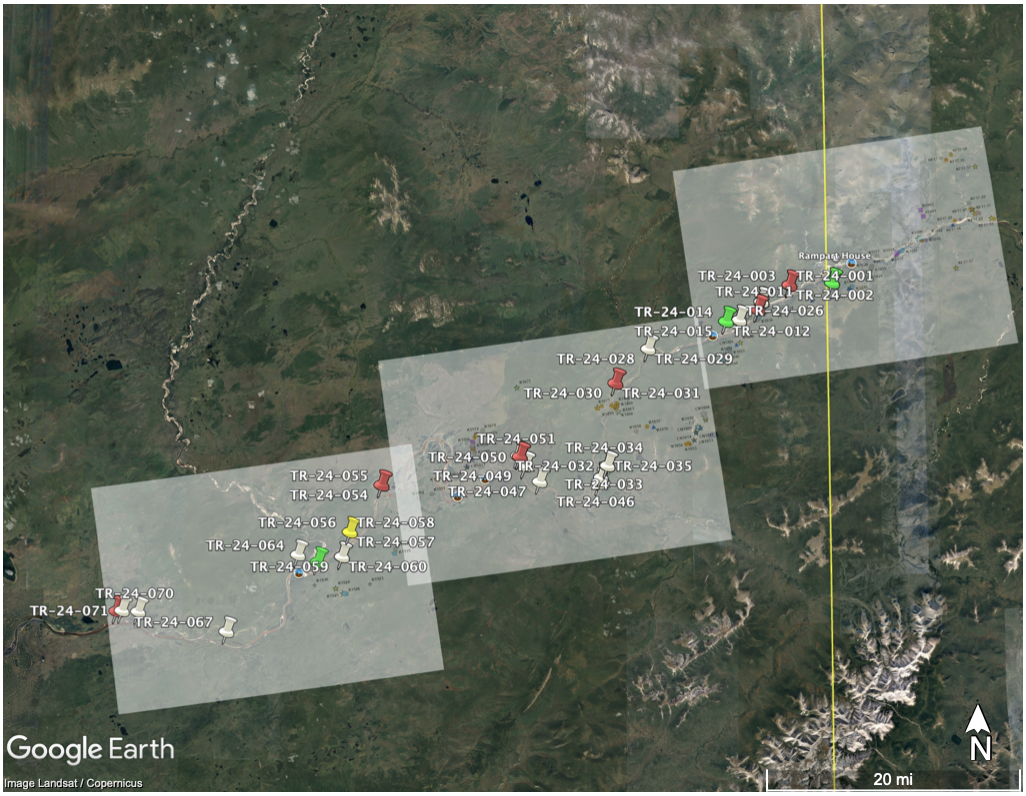

Satellite view showing the specific locations along the fault line where samples were collected.

That's what I spent my time figuring out. Usually, dating a fault involves analyzing calcite veins with a method called "Isotope Dilution." It's incredibly accurate, but typically requires rare, expensive machines and days of complex chemical filtering called "column chemistry".

I wanted to see if I could democratize the process—basically, could I get high-precision dates using standard lab equipment and skipping the slow chemical work entirely?

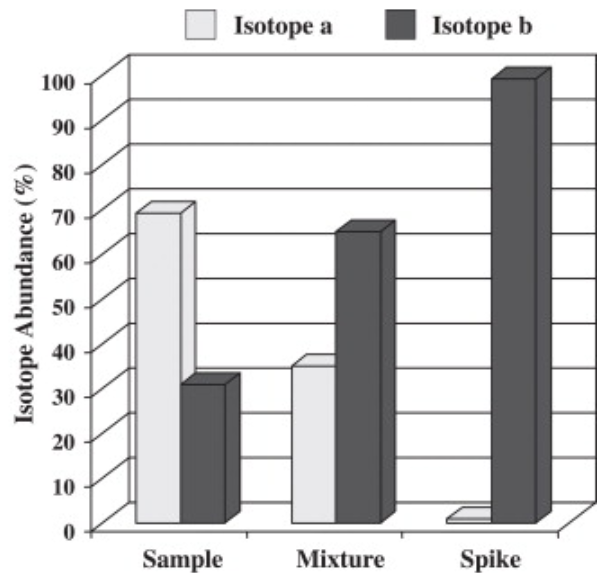

A diagram illustrating the "Spike" method. By mixing the unknown sample with a known tracer, the age can be calculated mathematically without requiring perfect sample purity.

I developed a workflow that bypasses the chemical separation by using a "spike"—a tracer of known isotopes—and running it through a standard Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer. This makes the whole process significantly faster and far cheaper than traditional methods.

To prove it worked, I tested the method on a reference rock with a known age and got 235 ± 21 million years, which perfectly matched established records. Once I knew the technique was solid, I dated the unknown Alaskan fault samples.

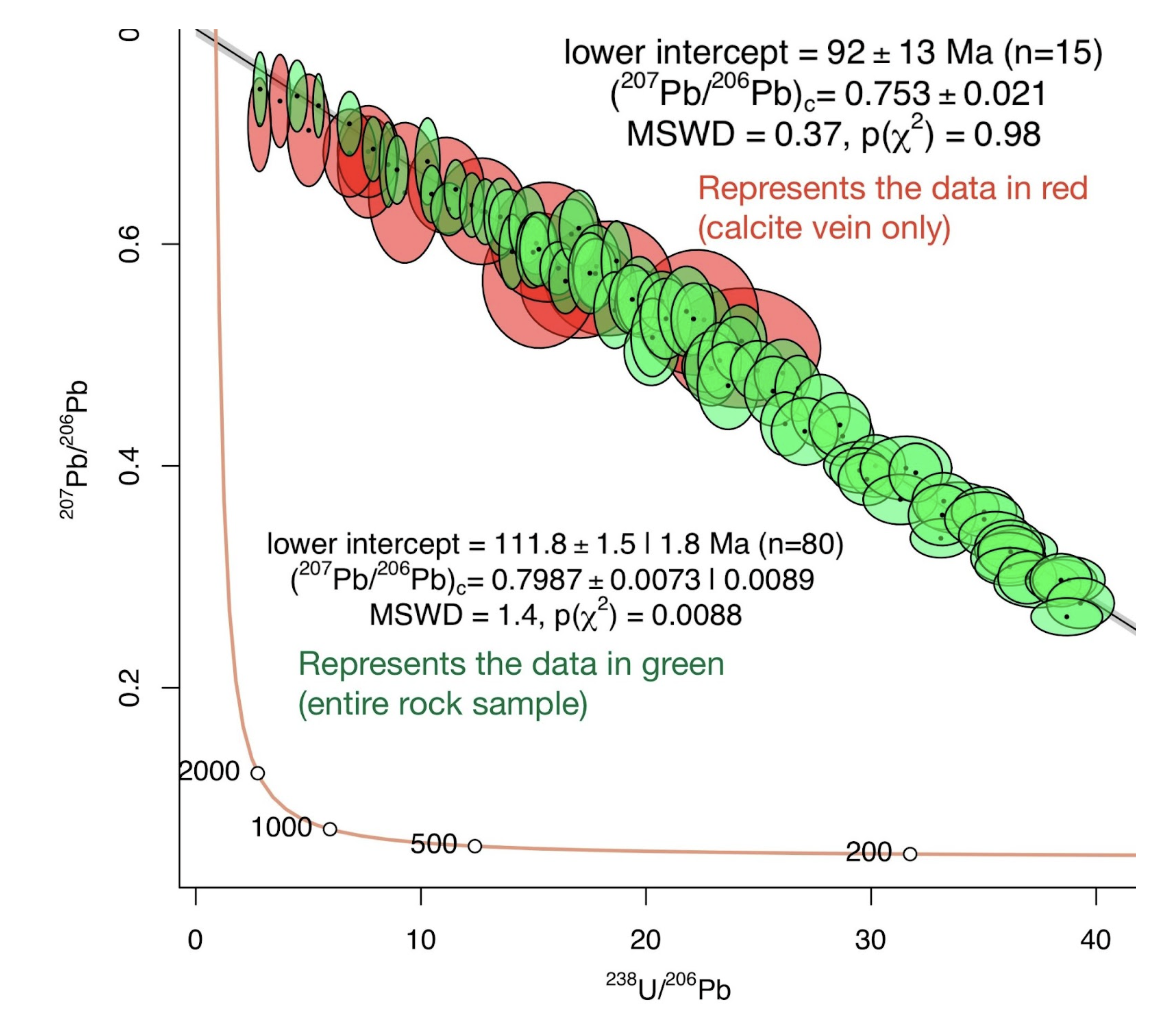

The tight alignment of the red and green data points serves as mathematical proof that the dating method worked, confirming the age of the fault activity.

The data confirmed that these faults were active roughly 120 million years ago, right in the Cretaceous period. This effectively backs up the theory that the Porcupine Fault System did accommodate the opening of the Arctic Ocean.

Weirdly enough, I also found that some parts of the fault were chemically "reset" much more recently—less than 10 million years ago—which suggests this ancient system is still geologically active today.

Beyond just solving a piece of the Arctic puzzle, this project showed that we can make geochronology much more accessible.